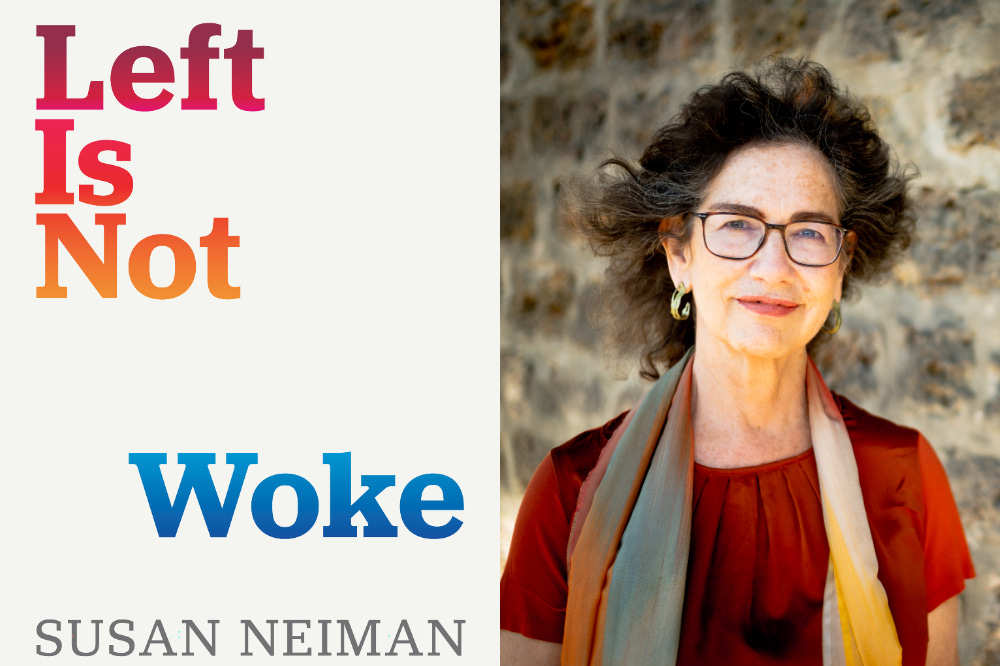

Susan Neiman's "Left Is Not Woke" (2023)

A critique of identity politics & ideas for an alternative path forward for the left

A NOTE TO READERS: Last week, I posted about Kwame Anthony Appiah’s The Lies That Bind and opened with sarcastic ridicule of those in power and their supporters. A dear reader told me my words felt personally hurtful, which made me reflect on my tone.

I’ve since apologized and revised the post to express my concerns rather than contempt. While I believe fear and moral outrage are valid, I don’t want to contribute to the culture of insults that dominates discourse. I won’t avoid sharp critique, but I’ll be mindful of how easily ridicule becomes toxic.

With that in mind, I continue my series on left-of-center critiques of identity politics. Let’s spend some time with Susan Neiman’s book.

Who is this person?

Susan Neiman (born 1955) is an American-German-Jewish philosopher who grew up in Atlanta during the Civil Rights era and today makes her life in Berlin. She is a moral philosopher, essayist and public intellectual who has extensively studied the Enlightenment and its bearing on moral politics today. Prof. Neiman directs the Einstein Forum in Potsdam.

Why Neiman wrote this book

Neiman argues that “wokeness,’’ which she equates with identity politics1, has misguided much of the left. She argues that several of woke politics’ main philosohpical foundations are contrary to the central principles of what it means to be on the left.

Writing as a socialist and leftist, Neiman stresses that this is not a right-wing “woke-bashing” book. Rather, it’s a book about how identity politics has parted ways with “the philosophical ideas that are central to any left-wing standpoint: a commitment to universalism over tribalism, a firm distinction between justice and power, and a belief in the possibility of progress.”2

To those three ideas, Neiman adds another political distinction:

“What distinguishes the left from the liberal is the view that, along with political rights that guarantee freedoms to speak, worship, travel, and vote as we choose, we also have claims to social rights… …things like fair labor practices, education, healthcare, and housing… …these, and other social rights to cultural life, are codified in the United Nation’s 1948 ‘Universal Declaration of Human Rights.’”3

As a leftist, she argues that identity politics hinders progress by overemphasizing differences, limiting cross-group empathy, dismissing universal equality movements, rejecting neutral rights as progressive goals, and denying that meaningful social progress has been made in American history. Also for Neiman, woke politics are intensely drawn to acts of unmasking, and in particular, unmasking the hypocrisies and failures of progressives and liberals.

Neiman adds that “the woke” are not very good at proposing political ideas strategically designed to persuade the masses and grow their base of support. Instead of working with center-left coalition partners to strategize to win elections and at least achieve partial progress, the woke are more interested in movement politics that pursue uncompromising public policy demands and engage in dogged attacks “unmasking” center-left candidates, which contributes to repeated election losses to reactionary candidates.

In this vein, Neiman quotes the American philosopher and historian of ideas, Richard Rorty:

“… (this) is exactly the sort of left that the oligarchy dreams of, a left whose members are so busy unmasking the present that they have no time to discuss what laws need to be passed to create a better future.”4

Neiman believes that the emotions that motivate “the woke” are noble and are the same ones that have motivated liberals and leftists for centuries: outrage over injustices; compassion for marginalized and oppressed groups; and determination to manifest the energy and courage to act in solidarity with the disadvantaged and mistreated.

What she hopes her book will do is convince many people who have fully embraced identity politics to reconsider some of the theories that undergird it. She hopes “the woke” will find their way back into the left-liberal political tradition that is grounded in the values of the Enlightenment (with some modern revisions), especially because the rise of fascism in our time can only be defeated by a broad and effective left.

This book is part love letter to and defense of the Enlightenment. Neiman thinks that identity politics has misconstrued the Enlightenment as a “racist, sexist movement” that aided European colonization and falsely promised progress. No, she argues, it was something quite different entirely, and we need it badly in this hour.

Channeling Appiah on the complexity and nuance of personal identity

Neiman shares many of the views of Kwame Anthony Appiah and even quotes him. (My last blog post was about his book The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity.) She argues that the identities that identity politics emphasizes (race, gender, sexual orientation, post-colonial nationality, etc.) are experienced by different individuals in vastly idiosyncratic ways, but that identitiy politics tries to flatten or simplify how those identities are experienced. This results in many of the people in these identity groups being inaccurately represented.

Neiman and Appiah see a lot of essentializing going on in identity politics. They note a common occurrence in parts of the left: the phenomenon in which someone who is part of a marginalized identity group expresses dissent from the claims of the group’s leaders, and then is told by others in the group that they are suffering from internalized oppression and need to get educated further so that they are able to see things “as they really are.” Neiman is deeply opposed to this kind of intellectual group pressure that stifles questioning. It results in a lot of people who might have been politically active instead walking away feeling misjudged and bitter about progressive politics.

Against victimhood as the bestower of moral or political authority

Neiman writes:

“Identity politics embodies a major shift that began in the mid twentieth century: the subject of history was no longer the hero but the victim. … The impulse to shift our focus to the victims of history began as an act of justice. … Yet something went wrong when we rewrote the place of the victim; the impulse that began in generosity turned downright perverse. … Where painful origins and persecution were once acknowledged, as in Frederick Douglass’s narratives, the pain was a prelude to overcoming it. Prevailing over victimhood, as Douglass did, could be a source of pride; victimhood itself was not. … [U]ndergoing suffering isn’t a virtue at all, and it rarely creates any. Victimhood should be a source of legitimation for claims to restitution, but once we begin to view victimhood per se as the currency of recognition, we are on the road to divorcing recognition, and legitimacy, from virtue altogether. It’s a sign of moral progress that we no longer dismiss victims’ stories, as we did for so long; they deserve our empathy and, wherever possible, reparations. … [Jean Améry, an Austrian Jew who survived Auschwitz] wrote, ‘to be a victim alone is not an honor.’5

Neiman is very determined about this claim. She writes, “Cries of pain deserve a hearing and a response, but they are no more privileged a source of authority than careful arguments.”6 Continuing in this vein, Neiman quotes Jean Améry from his book, At the Mind’s Limits:

“We did not become wiser in Auschwitz … We perceived nothing there that we would not already have been able to perceive on the outside; not a bit of it brought us practical guidance. In the camp too, we did not become deeper… …in Auschwitz we did not become better, more human, more humane, and more mature ethically. … We emerged from the camp sripped, robbed, emptied out, disoriented — and it was a long time before we were able even to learn the ordinary language of freedom.”7

Also along these lines, Neiman quotes the contemporary American philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò:

“…pain, whether born of oppression or not, is a poor teacher. Suffering is partial, shortsighted, and self-absorbed. We shouldn’t have a politics that expects different. Opppression is not a prep school.”8

And she adds:

“Táíwò argues that trauma, at best, is an experience of vulnerability that provides a connection to most of the people on the planet, but ‘it is not what gives me a special right to speak, to evaluate, or decide for a group.’ He argues that the valorization of trauma leads to a politics of self-expression rather than social change.”9

Táíwò’s concern about a politics of self-expression rather than one that’s strategizing for how to achieve social change reminds me of a line I quoted by Mark Lilla in one of my previous posts in this series: “Democratic politics is about persuasion, not self-expression.”10

When Neiman writes these rather harsh takes on granting authority to political speakers who base their standing upon their group’s victimhood, she is drawing on an academic career spent studying and writing about how Germany has handled its confrontation with its Nazi past in the years since World War II. She critiques the way the current German government deals with Germans’ feelings of shame and remorse by giving legitimacy to some of the most nationalist and illiberal Jewish leaders because they are the ones who make the loudest claims to moral authority by reason of Jewish victimhood. She offers this warning:

“…there is no more successful example of identity politics, complete with the appeal to past victimhood, than the Jewish nationalism of Israeli politicians like Binyamin Netanyahu.”11

And elsewhere:

“…[the] view that the voice of pain is the most authentic leads Germans to prioritize those Jewish nationalist voices focused on Jewish victimhood. … [German guilt] has led Germans to ignore the voices of Jewish universalists — those of us who cannot shake the intuition that Palestinians, being human, have human rights that should be recognized. It was the universalist tradition in Judaism that produced the giants of German-Jewish culture, from Moses Mendelssohn to Hannah Arendt.”12

Neiman acknowledges that victimized groups hold moral and political authority in shaping historical understanding and in seeking restitution. However, she argues that victimhood alone does not confer wisdom or political legitimacy.

What do we want? The Enlightenment! When do we want it? Now!

Susan Neiman loves the Enlightenment, and she believes that, with proper adaptations, many of its core ideals and universal beliefs still show the way to a progressive politics that is inspiring, achievable and urgently needed in this period of resurgent fascism. Perhaps her biggest critique of identity politics is the way in which it has come to view Enlightenment values as invalid for the pursuit of justice.

“It’s now an article of faith that universalism, like other Englightenment ideas, is a sham that was invented to disguise Eurocentric views that supported colonialism. When I first heard such claims some fifteen years ago, I thought they were so flimsy they’d soon disappear. For the claims are not simply ungrounded: they turn the Enlightenment upside down. Enlightenment thinkers invented the critique of Eurocentrism and were the first to attack colonialism, on the basis of universalist ideas.” (italics hers)13

Neiman, like Yascha Mounk (about whom I posted two essays in this series), lays a huge amount of the blame for “wokism’s” rejection of Enlightenment ideals at the feet of Michel Foucault. She writes that Foucault and his ilk:

“…were united in viewing what they called ‘Enlightenment reason’ not merely as a self-serving fraud but even more as a domineering, calculating, rapacious sort of monster committed to subjugating nature — and with it, indigenous peoples considered to be natural. On this picture, reason is merely instrument and expression of power.”14

With Foucault also came the argument that “…every attempt to make progress entangles us in a web that subverts it.”15 Progress is impossible and those who claim to be working for it are either lying to you, or lying to themselves and to you without realizing it.

In contrast, Neiman argues that the Enlightenment drove real progress by challenging oppressive Church and state power through reason and universal human rights. While some Enlightenment thinkers justified colonization, others, like Diderot and Kant, fiercely opposed it. Despite its contradictions, she sees the movement as a revolutionary force against both European tyranny and colonial oppression. She writes that “the Enlightenment was pathbreaking in rejecting Eurocentrism and urging Europeans to examine themselves from the perspective of the rest of the world.”

Neiman disputes the arguments made by some post-colonial studies theorists that anything that came out of Europe, including Enlightenment ideas, is inherently oppressive and alien to the fight for liberation for colonized peoples. We shouldn’t make the mistake of saying “this is Western so its bad” because that makes the mistake of thinking of “the West” as a single, coherent thing without internal contradictions or battles of ideas. A more honest, and complex, analysis of the era of European conquest would tell a story in which an internally divided and fracturing Europe saw its traditional power centers attack and dominate peoples on other continents; furthermore, the non-European societies that were invaded were themselves internally divided and morally flawed.

This isn’t a justification for colonizing — it’s just an honest description of the complex nature of societies, including those that conquer or get conquered. A major point Neiman makes is that empires have been normative all over the world for eons, and most of them have brutally subjugated and colonized others. Enlightenment writers were the first we know of to criticize their own rulers’ colonialism.

The Enlightenment is important to humanity’s hope for a better, more just and humane world not because it originated in Europe, but because its ideas were an example of human revolt against unjust power structures claiming to be God-ordained or “natural,” and because the revolt insisted on ideas like the right to think for oneself about religious matters and the right to have a say in how one is governed regardless of one’s social station. It shares intellectual and moral connections to other non-European social, religious or political revolutions that challenged unjust political and social orders.

For Neiman, identity politics — and perhaps post-colonial studies in particular — often misses a crucial aspect of all human societies: they are not solid objects. Societies contain internal contradictions, competing centers of power, and sometimes they include brewing revolts and factions seeking to radically overturn longstanding beliefs or power structures in an effort to achieve greater justice. The Enlightenment was first and foremost a revolutionary movement seeking to challenge, overturn and replace unjust systems of power in Europe, and its value to us now comes from the universal truths that it uncovers and expresses, albeit imperfectly. Its best ideas are the inheritance of all of humanity.

Neiman argues that the contemporary thought leaders embraced by identity politics tend to be those who reject the Enlightenment because of its European taint. She writes, “While contemporary universalist thinkers of color are ignored, universalist elements of classic anti-racist and anti-colonial thought are downplayed.”16 To bolster her perspective, she highlights some of the post-colonial thinkers of color whom she argues get ignored.

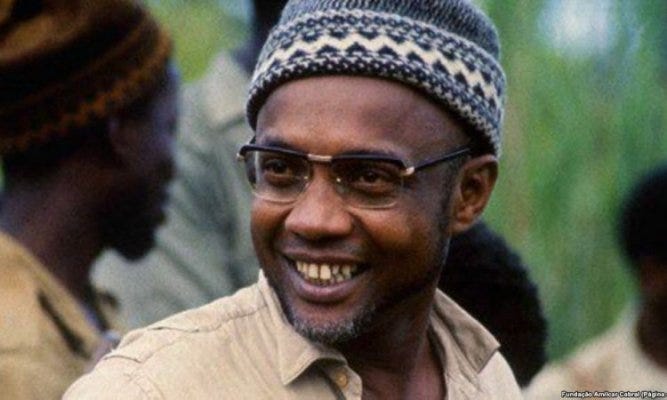

Neiman cites Amilcar Cabral (1924 - 1973), who led the battle for independence for Guinea and the Cape Verde Islands, and whom she says was known for urging colonized peoples in Africa to engage in a “re-Africanization” of their minds. Yet, Neiman writes of him:

“Instead of dismissing every cultural concept suspected as European, Cabral argued for adopting from other cultures ‘everything that has a universal character, in order to continue growing with the endless possibilities of humanity.’”17

Cabral, she says, also rejected the idea that indigenous cultures should be regarded as somehow exempt from the banalities and flaws that any other cultures all have. She quotes him from his essay, “National Liberation and Culture”":

“All culture is composed of essential and secondary elements, of strengths and weaknesses, of virtues and failings, of factors of progress and factors of stagnation or regression.”18

She also makes the case that the French Afro-Caribbean psychiatrist and noted anti-colonial voice Frantz Fanon also supported the need for universalism as a key component in creating a just world. In Fanon’s case, Neiman writes that he argued that we need “new concepts of humanity, and the related concept of universalism, to remove the taint of imperialist, fraudulent versions of those ideas,”19 but that rejecting universalism completely would be a mistake.

Justice and progress are real and are possible

One of the key components of a leftist standpoint is the belief that progress is possible, and that progress has been made at different times in the past. (Neiman is quick to say that regression is also possible, and has also happened.)

In the political culture of identity politics, she claims, there is a deep distrust that progress is possible for oppressed groups, especially if that progress is part of a vision that seeks a just society based on universal principles and equal rights for all. Neiman sees this as a recipe for a left that can’t identify what a future society that provides justice for all would look like, much less offer the public a vision for how we move ourselves from the problems of the present towards that better future for all.

She blames Foucault for shaping generations of political theorists who have embraced his belief that all discourses, including those expressing goals of progress and justice, are ultimately masking struggles for power.

“In the modern era, said Foucault, power is hidden and diffuse, expressed through a network of structures we rarely perceive. There is no point we can locate and challenge, especially since we are implicated in the very networks that constrain us.”20

Foucault and his circle believed that movements for universal justice, even if they are sincerely motivated, always fall victim to the insidious ways in which existing unjust power structures reconfigure and redistribute themselves through attempts at reform. There is no actual possibility of achieving justice, or an end to racism, or an end to other forms of longstanding oppression. There is, ultimately, only the possibility of renegotiating shares of power held by different groups. This thinking leads to lines of argument that, for example, deny that any real progress on racial justice was achieved through the American Civil Rights movement, or that it is a fool’s errand to build a movement for progress upon the ultimate goal of achieving a society that transcends racism.

She writes:

“Most woke activists reject universalism, and stand by discourses of power, but they’re unlikely to deny they seek progress. It would be easier to believe them if they were willing to acknowledge what some forms of progress had achieved in the past. Showing how each previous step forward led to two twisted steps back can be intellectually dazzling. There are enough instances of injustice to unmask so that several lifetimes won’t suffice to do it. But without hope for putting something else in its place, such unmasking becomes an empty exercise in showing your savvy.”21

She also adds, “From the fact that some moral claims are hidden claims to power, you cannot conclude that every claim to act for the common good is a lie.”22

She acknowledges that there are plenty of examples of universalist-based attempts at social justice being abused by bad actors, as well as plenty of examples of sincere attempts at progress going awry and resulting in counterproductive results. But she flatly rejects the idea that no progress has ever been achieved, and she writes from her personal experience as a Jewish child growing up in Atlanta in the 1950s and 60s.

Neiman’s mother was deeply involved in the Civil Rights movement at the time, and her family’s synagogue was bombed by white supremacists. Neiman remembers when everything in her world was segregated and it was illegal for her to swim with her Black friends. For Neiman, the blood, sweat and tears that thousands of activists, Black and white, spent first to abolish slavery, then to abolish Jim Crow (which Neiman refers to as the “era of racial terror”), and then to open up greater access for Black Americans to higher education and upward economic mobility are sacrifices that ushered in real progress. She argues that it’s absurd to claim otherwise. No Black American who lives today would prefer to live during Jim Crow, and none who lived during Jim Crow wished they were enslaved.

The way she puts it, the US has moved from several centuries of chattel slavery, to a post-slavery era of segregation and racial terror, to a present era of unprecedented freedoms and opportunities taking place alongside severe racial backlash and enduring structural racism. That is a story that says there is still tons of work to be done; but, she argues, that is also a story of hard fought progress.

For Neiman, the left’s path is one that keeps fighting effectively for further progress. And the fundamental argument against racism is based in the Enlightenment value of the equality of all human beings. She writes, “To stand on the left is to stand behind the idea that people can work together to make significant improvements in the real conditions of their own and others’ lives.”23 And she adds, “Give up on the prospect of progress, and politics becomes nothing but a struggle for power.”24

What is to be done

One of Neiman’s major arguments in this book is that many of the major philosophical ideas that form the foundation of identity politics are politically reactionary ideas. She argues that claims that people of different identity groups can’t adequately understand each other, and that they should accept that the world is one in which different identity groups always are contesting each other for power, is an idea that has traditionally been core to right wing xenophobic groups. She adds that disbelieving that progress towards universal justice in a multicultural, democratic society is possible is also a core belief of the far right. Basically, for Neiman, tribalism is a right wing thing, even if it’s being applied by oppressed and marginalized groups.

She writes:

“The woke call to decolonize thinking refects the belief that we will not survive the multiple crises we’ve created unless we change the way we think about them. I agree that we desperately need fundamental changes in thinking, but I’ve urged another direction. For, as I’ve argued, the woke themselves have been colonized by a row of ideologies that properly belong to the right.”25

What she hopes is that people involved in identity politics will shift their focus to that which is broken socially and economically in the U.S. as a complex, whole society. She sees a majority of Americans struggling under a corporate capitalist economic system that has been facilitating a transfer of wealth from the poor and middle classes to the richest few. This system is one that has for the most part maintained most Americans’ rights to free speech, suffrage, freedom of religion, and the other items listed in the Bill of Rights (though all of that is increasingly in jeopardy). But it is a system that has denied Americans what she calls social rights as championed by leftists — the rights to a good education, decent housing, healthcare, access to libraries and parks and the arts, and decent eldercare.

The result has been a growing percentage of the population facing economic decline and growing fears about their own future and that of their children. Neiman also sees the impacts of decades worth of repetition of the message that a corporate neoliberal economic order with little safety net is the only realistic kind of economy we can have as a contributing factor to a lack of determination by the American public to demand sane policies to avert climate collapse.

In addition, Neiman sees Americans becoming increasingly disconnected from each other, influenced by the loss of a once nationally shared common sense that believed that overcoming social injustices including racism and sexism is not only possible but is the long term mission of the nation. Right wing propagandists have fueled a revolt against the idea that achieving a true society of equals is core to American identity, and on the left the leading thinkers of identity politics have shepherded a parallel abandonment of this value.

In explaining the rise and appeal of the neo-fascist American right, she quotes Thomas Piketty:

“When people are told that there is no credible alternative to the socioeconomic organization and class inequality that exist today, it is not surprising that they invest their hopes in defending their borders and identities instead.”26

Neiman’s book calls for the renewal of leftist politics grounded in the core leftist values described earlier in this post, and she emphasizes that the threat of fascism makes this a time when all anti-fascist voters need to be able to band together. This is a time for coalition building and the compromises and creative strategizing that it needs in order to win elections.

Near the end of the book, Neiman makes a three-question appeal which I found very moving:

“Because universalism has been abused to disguise particular interests, will you give up on universalism?

Because claims of justice were sometimes veils for claims of power, will you abandon the search for justice?

Because steps towards progress sometimes had dreadful consequences, will you cease to hope for progress?”27

Some questions / concerns I have after reading Appiah and Neiman

What about the upside of unmasking?

Neiman spends a lot of time describing identity politics as having a bottomless appetite for unmasking injustices that lurk just beneath the surface of the everyday parts of American society, and a special appetite for unmasking Democrats for being “faux progressives.”

I’m convinced that that really is a phenomenon that has made leftwing-to-centrist coalition building nearly impossible. But here’s a concern I have. Unmasking helps members of oppressed groups recognize and break free from the distorted narratives imposed upon them by mainstream society.

Having the experience of unmasking the gaslighting with others who also “get it,” is a transformative life experience. The personal liberation a lot of people feel when they finally have the support of peers who show them how they’ve been betrayed and lied to and why they are actually worthwhile human beings — well, that is precisely the game changing experience of “getting woke.”

Feeling sad about the loss of an evocative piece of language

I feel sad that what started as language describing a deeply mentally and spiritually liberating experience — “getting woke” — is now a term of derision, not just on the right but in parts of the left as well. I’m also suspicious of a subtle racism at play in the public beating that’s been given to “being woke,” because this language comes from African-American slang.

That said, I think the language of wokeness is politically demolished at this point. It has been weaponized so effectively by the right as a term of revulsion, and it has become such a strong symbol of what frustrates people on the left about identity politics, that I can’t see a useful political future for it.

But something sad has happened regarding this language. “Getting woke” is similar to metaphoric language used by lots of Americans in many different contexts. We hear calls to “wake up” all the time, especially from the far right. We hear about peoples’ spiritual awakenings. Even the term “enlightenment” involves a kind of awakening. Among all those terms, it is a bit of metaphoric language that came from the Black experience that is taking the fall for a kind of intersectional identity politics that has been around much longer than the language of “woke” has been.

One last thing - a lingering doubt I have

I worry that my understanding of identity politics comes solely from its critics. I haven’t read Bell, Crenshaw, or Spivak, and my college readings of Foucault and Said are a blur. Mounk suggests that popular identity politics sometimes distorts these theorists' ideas, making me question whether I’ve engaged with them fairly.

What’s next with this series

Having read and shared thoughts with you about Yascha Mounk, Mark Lilla, Francis Fukuyama, Kwame Anthony Appiah and Susan Neiman, I’ve learned a lot. I hope my essays describing some of their ideas and sharing my own comments and questions has been useful to you. I have as many questions now as I had when I started reading these writers, but they are different questions.

What I want to try next is to take a shot at writing up a progressive political platform based on the things these writers have argued would make for a viable and appealing American politics of the left. I know that may sound like a grandiose project, but I kinda want to see for myself what a leftwing politics like that might look like. I’m not promising I’ll get it done, but if I do, you’ll see it here soon.

p. 2.

pp. 1-2.

p. 60. Rorty’s quote is from his 1998 book, Achieving our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America.

Selected passages from pp. 15-17.

p. 51.

pp. 17-18.

p. 18.

p. 18.

p. 117, The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics by Mark Lilla.

p. 19.

p. 49.

pp. 31-32.

p. 66.

p. ??

p. 52.

p. 53. The Cabral quote she cites is from a 2011 documentary called Cabralista.

p. 53.

p. 53.

p. 61.

p. 108

p. 64.

p. 93.

Ibid.

p. 127.

p. 137. The quote is from Picketty’s book Capital and Ideology.

p. 140.