Yascha Mounk's "The Identity Trap" (2023) - Part 1 of 2

An intellectual history of today's identity politics, a critique, and ideas for an alternative kind of progressive politics

Hey everyone. I have found that it’s taking more time and more words than I anticipated to write up a summary and personal response to the first of the four books I’ve recently read from left-of-center writers critiquing identity politics. So here is the first of two blog posts on Yascha Mounk’s The Identity Trap for your consideration.

Who is this person?

Yascha Mounk is a 42-year-old German-Jewish-American political scientist and author who serves as Associate Professor of the Practice of International Affairs at Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies. Over the past decade, he has written numerous books and articles analyzing and warning about right-wing populism in the US.

He describes this book, The Identity Trap, as an analysis of and warning about the impacts of left wing identity politics in the US. He says it is an important companion to his previous work. Mounk describes himself as a progressive supporter of liberal democracy. He promotes a progressive politics that stresses what human beings have in common over their differences, and that aims for a society in which unjust treatment of people based on their differences ends, and in which these differences no longer serve as determiners of power, opportunities, wealth, safety and dignity.

The intellectual history of identity politics according to Mounk

Mounk offers a history of influential ideas that he argues have built upon each other and converged to develop contemporary left wing identity politics. Here’s a lightning-fast overview of the thinkers and ideas he covers (don’t worry if you’re not sure what some of the terms mean — that will come later):

Mounk starts in the 60s with the French philosopher and historian Michel Foucault, and the early proponents of deconstructionist and post-modernist theory. From there it’s on to Edward Said’s work on discourse analysis, followed by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s work on strategic essentialism. Mounk then pivots to Derrick Bell’s and Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work on critical race theory. Then he addresses the tenets of standpoint epistemology as developed by Donna Haraway and other feminist philosophers (even though these ideas preceded critical race theory). Then Kimberlé Crenshaw returns as the person who coined the term intersectionality in an influential 1989 paper, ushering in a new framework for societal analysis. Finally, Mounk spends some time discussing very recently popular thinkers like Ibram X. Kendi and Robin DiAngelo and their claims about what needs to happen to dismantle racism, sexism and other -isms and -phobias.

Mounk acknowledges that there are a lot of people and ideas that he has left out of this progression, and that it is possible to put together alternatives to this list. He also states his discomfort with the terms people often use to describe this kind of politics. He doesn’t like the terms “idenitity politics” or “woke,” because he says they are polarizing and interfere with the opportunity to have a mature, researched and nuanced debate about these ideas.

He says that no alternative term has come into the public square, so he offers his own: the identity synthesis. He admits that this term doesn’t roll off the tongue. I agree. One thing that doesn’t work for me in his book is his attempt to make the identity synthesis stick as a term. I just don’t believe that’s going to be what we call this. I was thinking that a term that makes sense to me would be something like intersectional identity politics, but then I felt like that term had one to many long words in it to be helpful, so I have settled on sticking with good old identity politics.

Mounk also claims that starting around 2010 the political movement promoting identity politics burst out of the confines of academia and rapidly swept through American cultural and educational institutions, with parts of government and the corporate business world quickly following. He writes that the shock of Trump’s first election win accelerated what he calls “the short march through the institutions” that identity politics performed in the second half of the 2010s.

This is another claim of his that doesn’t feel quite right to me. As someone who went to college in the late 80s / early 90s, much of what Mounk is describing about identity politics was already in full bloom on campuses and playing a role in lots of mainstream cultural scenes (including generating right wing radio outrage over the spread of “politically correct” elite opinions). Furthermore, one of the key elements of identity politics — a pivot away from advocating for neutral rules and colorblind goals and towards certain kinds of group separatism — are as old as the debates between MLK and Malcolm X. In other words, Mounk may be right that a new, energetic wave of identity politics moved from academic circles into mainstream culture in the 2010s, but I found it odd that he didn’t argue that key elements of identity politics have been part of American culture and its debates on the left since at least the 1960s.

Nevertheless, Mounk’s book does a great job of teaching readers about each of the foundational ideas he describes. I learned a lot reading his succinct and clear descriptions of what ultimately are complex literary, social, historical and political theories. And even though he ends up critiquing aspects of each of these ideas, he gives respect to each of the innovative thinkers who developed them, and he says that the circumstances in which each of these ideas arose made it understandable that they did. Going even further, he argues that we have much to learn from these ideas and that an outright rejection of any of them would be an intellectual and moral mistake. For me personally, this is one of the ways in which his book really shines.

Mounk’s intellectual history of identity politics: a closer look

Michel Foucault: Deconstructionism and Post-Modernism

Mounk writes that the French post-modernists in Foucault’s orbit responded to the shocking revelations that came out of the Soviet Union after Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953. As the USSR’s new leaders publicly aired the dirty laundry of Stalin’s maniacal and mass-murderous history, French left wing intellectuals, who had been ardent Marxists, split. One group doubled down on Marxism. Foucault and his crew broke away, developing a new theory of society, politics and power.

They claimed that all meta-narratives — the great mythic stories that governments and religions tell us to believe — should not be trusted. Furthermore, Foucault argued that unjust power structures are reinforced not just from the top down, but through the constant thrum of everyday discourses in which people unwittingly confirm and uphold beliefs and attitudes that support the status quo. These discourses should be deconstructed so that their relationships to power structures are revealed.

Also, the post-modernists developed the idea that knowing the objective truth about social, political or cultural situations may be impossible. Each person, as a subject, has a unique experience and a unique set of responses to what happens in their lives. Multiple truths co-exist. Understanding the subjective perspective of many different people is essential to getting closer to the truth of the matter, though there may not be an “actual” truth that is possible to know. There’s lots more going on in Foucault’s work, but these are the key ideas Mounk identifies for his anlaysis.

Edward Said: Discourse Analysis

Mounk writes that Said accepted much of Foucault’s thought, but that he was disappointed that the impact post-modernist and deconstructionist theory was having in the world was primarily to reshape university literature departments and encourage politically irrelevant “word games” and deep dives into the impossibility of ever really knowing anything.

Mounk writes: “For Said … the task of a critic … was to ‘commit himself to descriptions of power and oppression with some intention of alleviating human suffering, pain, or betrayed home.’” (p. 43) Said took the idea of analyzing discourses and argued that we should focus on meta-narratives — grand discourses promoted and propagandized by powerful, oppressive nations, empires or cultures. Our aim should be to deconstruct and dispute these oppressive discourses, and, as Mounk describes Said’s thought, “…the goal of cultural analysis should be to help the oppressed. … The goal was to change the dominant discourse in such a way as to help the oppressed resist the oppressor.” (44)

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak: Strategic Essentialism

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak is a complicated figure whose thinking has evolved throughout her long career as a literary theorist and critic. Mounk is focused on a distinct period in Spivak’s work, when she focused on emphasizing the experiences and needs of subaltern women in post-colonial India. (Subaltern people are those who are oppressed and disempowered in an imperial / colonial system.) A group she participated in, the Subaltern Studies Collective, concerned itself especially with peasants, poor workers and people of low caste whose beliefs and political agendas were often overlooked in Marxist-oriented left wing discourses about post-colonial issues in south Asia.

Spivak took issue with some of the ways that international feminist movements and Marxist movements were sometimes divorced from the lived experiences of the poorest of the poor and the most oppressed of all in India. She argued that there were specific forms of oppression that people in these categories of society experienced, and that the powers oppressing them applied group labels to them that they used to perpetuate their oppression. Although these group labels did not constitute true essential identities, Spivak argued that it was necessary for people in these groups to use these identities to fight for their rights and their liberation from horrible conditions. This is how she developed the notion of “strategic essentialism.”

A person who is being oppressed in India because they are (a) brown-skinned and not English, (b) of low caste, and (c) female is not, in their essence as a human being, a “non-white low-caste woman.” But that person, according to Spivak’s argument, has no chance of fighting to improve her life without banding together with other low-caste women and calling out the specific injustices they face and demanding change. Spivak also argued that when people in these kinds of extremely disempowered positions are also illiterate and have zero access to political power, money or mass-communication tools, it is the responsibility of intellectuals and critics in their country to speak for them and to use these identity labels for the purpose of seeking justice.

All this notwithstanding, Spivak warned that these identities were not, in fact, essential to any individual person, who may regard their personal identity in myriad ways that are unique. She distrusted essentialism, but she advocated for strategic essentialism as necessary and constructive in specific situations.

Mounk argues that her ideas paved the way for other oppressed groups in other societies, including the US, to organize and advocate on behalf of the identities that may have been constructed and imposed upon them by the powers that have dominated them. This explains why identity politics will sometimes proclaim “race is a construct of the oppressors” while also proclaiming “you need to be a member of X racial group to truly understand the nature of the oppression taking place.” Spivak’s work dovetailed with Said’s in making sure that the tools of deconstructionism and post-modern questioning of the validity of any truth claims would not prevent the poor and oppressed from organizing along lines of identity to fight for their liberation.

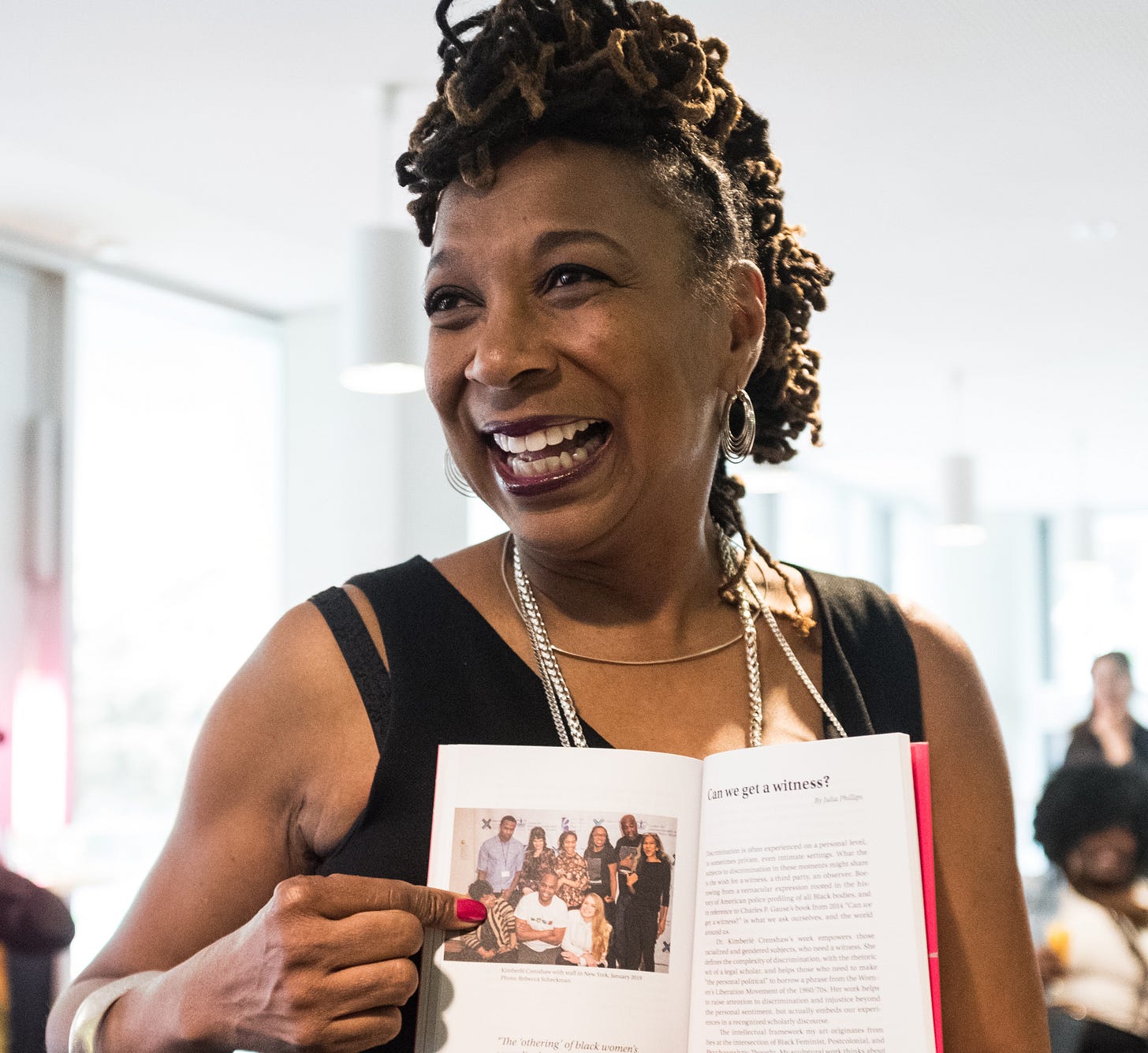

Derrick Bell and Kimberlé Crenshaw: Critical Race Theory

Mounk introduces us to a former Harvard Law professor, Derrick Bell, and one of his most influential students, Kimberlé Crenshaw, with a narrative that is moving and shows great respect for the experiences they’ve had and the sincerity of their convictions as they went on to pioneer critical race theory.

In his work at the NAACP, Bell led over 300 lawsuits that sought to enforce different provisions of Brown v Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. Even though those landmark federal laws led to major changes in non-descrimination practices in public schools, restaurants, hotels and housing, at the same time there were endless examples of white communities using clever workarounds to avoid following these laws. There were also racially unjust outcomes that followed the correct implementation of some civil rights laws.

For example, in working and middle class suburbs where banks and real estate agents complied with new non-discrimination laws, Black Americans began to move in. But then whites would move out. True racial integration in housing was supposed to lead to economic upward mobility for the part of the Black community that had the income to afford to move into middle class white neighborhoods that had previously been off limits to them. An anticipated positive outcome was that finally Black Americans could begin the process of home ownership leading to the building up of family wealth across generations (which depends on housing prices generally going up over time).

But because of white flight, housing prices would only continue to rise in new, farther out white suburbs, while the newly racially integrated suburbs would see their housing values plummet as whites fled. Schools — usually funded by hyperlocal property taxes — got better and better in the newer white suburbs, but stagnated under limited resources in what were becoming new Black neighborhoods. Meanwhile, in poorer Black urban neighborhoods, the loss of the middle class Black tax base to newly integrating suburbs caused the budgets for their schools to shrink, exacerbating racial inequalities in the public education system.

With mandatory school desegregation came federally court ordered busing of Black children from poorer neighborhoods to desegregate overwhelmingly white suburban schools. Many teachers who had taught in schools serving Black communities lost their jobs as the student base dwindled through desegregation. Many Black students arrived in white-dominated, wealthy schools whose almost all white teachers often had little training or guidance in how to help make what was a big cultural shift for all their students play out well. (I witnessed this at my suburban St. Louis high school in the mid-80s.)

Students often segregated themselves along racial lines within these “desegregated” schools, and Black students whose previously inferior schools hadn’t prepared them for academic success in their new schools often struggled without support systems to help them catch up and manage the many stresses of being the new “outsider” kids who were also having to ride over an hour each way to school. Bell was influenced by a group of Black parents in Boston who wanted the courts to stop ordering that their kids be bused to far-off white-dominant schools and instead order that adequate funds be provided to hire really good teachers for their kids in their own neighborhood schools. Bell realized that in a way this demand bore the whiff of “separate but equal,” but it was what this group of Black parents wanted based on their unsatisfactory experiences with the desegration system. They wanted their kids’ test scores to rise, and they believed that could happen with really excellent teachers in their nearby schools.

Another phenomenon to consider: in 2009, the median weath of white American households was 20 times that of Black American households. That was a peak partly caused by the financial crisis of 2008. In 2021, median white household wealth was over 9 times that of Black. You can see from this chart from Pew that over the past 25 years the ratio of white household wealth to Black has tended to be between 8 and 11. The 2008 financial crisis caused Black families much steeper losses in total household wealth than whites, perhaps because a crashing housing market hits people with lower housing values hardest. But the main point here is that over nearly 40 years the ratio of white to Black median household wealth has remained basically in the same range.

Anyway, these are just some of the reasons that led Bell and Crenshaw, both working in the specialized field of legal academia, to develop a new analysis of the impacts of laws and government policies upon people of different racial groups. This analysis argued that the legal successes of the civil rights movement were pretty illusory. There were too many ways for whites to evade, avoid or reinterpret their way out of actualizing the intended social and economic changes envisioned by the ideals of the civil rights era. And laws that sought to enforce colorblind standards too often served to fail to lead to actual changes in the amount of wealth, opportunity, personal safety or dignity experienced by Black Americans.

Bell and Crenshaw concluded that racism in America is structural — deeply embedded and intertwined within the many social and economic systems, formal and informal, that make up society, and that racism is a permanent feature of our society. There’s so much ignorance of the massive advantages that white households have, in terms of wealth, networking, social respect and access to opportunities, that race-neutral or meritocratic laws and systems don’t actually create a level playing field. Laws seeking to change society so that everyone is treated equally regardless of race fail to do so in practice, and actually serve to provide a false narrative of equality when equity — the achievement of truly equal shares of power, opportunity and dignity — remains lopsidedly unfair.

Similarly, “objective” analyses of racial progress fail to include meaningful study of the self-reporting of Black and brown Americans. The lived experiences of many of these Americans reveal a society that remains a tapestry of daily disadvantages, humiliations, dangers to physical safety and painful invisibility. In settings that bring white and Black Americans together, seemingly neutral principles like “free speech” often get used to allow dominant voices defending the status quo to discredit or inhibit testimony from people in racial minority groups. Even free speech can be a supporting element for a structure that is perpetuating racism.

According to Mounk, critical race theory rejects the fundamental ideals of the civil rights movement: in particular, the belief that the way to defeat racism is for all Americans to demand that their country live up to the colorblind ideals of the Declaration of Independence, as MLK called for in his “I Have a Dream” speech. Rather, because racism is a permanent and deeply seeded part of American society, legal remedies should focus on the racial identities of citizens and prioritize redistribution of resources to racially oppressed groups. Laws should make determinations about benefits and opportunities to citizens based upon their racial identities and take action to try to achieve equity between racial groups.

In addition, whites have work to do to educate themselves about the history of racism and about how racism continues to pervade and harm people of color, but it is not really possible for whites to truly understand the experiences of people in minority racial groups, and in order to serve as allies to the cause of combating racism, whites should follow the lead of Black and brown political activists as they make demands for structural changes to American society that will create greater equity if implemented.

Mounk describes critical race theory as embracing a fundamentally pessimistic view of America and the possibility of achieving the dream of all citizens being judged not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character, per MLK’s famous speech.

Donna Haraway and others: Standpoint Epistemology

Many years before Kimberlé Crenshaw helped organize a 1989 workshop at the University of Wisconsin - Madison that she called “Critical Race Theory,” Donna Haraway and other leading feminist philosophers and critics were developing a theory called standpoint epistemology. (Epistemology is the study of knowledge, or of how people acquire knowledge.)

This theory argued that a person’s perspective emerges in large part from their group identity and the social and historical situation in which they live, i.e. their “standpoint.” In order to understand a person in an oppressed group’s experiences, one must listen to their accounts of their lived experiences. Their lived experiences, a.k.a. situated knowledge, is superior to “neutral” or “objective” claims describing what is going on for them and others belonging to the same oppressed groups.

Some of the key research that Haraway and other feminist scholars, like Sandra Harding, did that influenced the development of standpoint epistemology was of the ways in which the medical sciences tended to design research and experiments that often presumed male anatomy as a default, or that rejected direct testimony from women when formulating medical treatment plans for women with various diseases or disabilities. They successfully exposed myriad examples of how studies and experiments designed by supposedly “neutral and objective scientists” often reflected various biases of the funders and implementors of the research. And of course, we all know that “science” has at different times given its stamp of approval to later discredited insideous beliefs such as the inferiority of darker skinned “races.”

Haraway et al called for widening the circle of inclusion in the development, design and implementation of scientific and medical research, and for even a field as proudly “objective” as science to make sure it seeks information from diverse groups of people, including historically oppressed groups, in its pursuit of accurate knowledge that serves humankind. The core ideas of standpoint epistemology moved beyond the study of science and medicine to social and political realities, and played a big role in the development of critical race theory.

Mounk is very sympathetic to standpoint epistemology. He argues in his book, however, that over time a more popularized and problematic variant of standpoint epistemology came into vogue in left wing political circles. He calls this variant “standpoint theory.”

Mounk writes, “In this popularized form, standpoint theory goes far beyond an exhortation to ensure that people from different backgrounds are involved in scientific research or political decision-making; it stipulates that there are some important insights that members of one group will never be able to communicate to outsiders.” (72) Mounk argues that that idea has morphed even further into a simpler and even more problematic variant: “the idea that I have ‘my truth’ — one that you have no right to question or critique on the basis of supposedly objective facts, especially if you do not belong to the same marginalized identity group.” (72)

Kimberlé Crenshaw and others: Intersectionality

In the course of her academic work in legal studies, Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” and it took off as a framework of analyzing social, historical and political aspects of society. Mounk writes, “As orignally conceived by Crenshaw, the concept of intersectionality had comparatively modest goals. It aimed to ensure that the law could deliver justice for people who suffered discrimination because they exhibited two disfavored characteristics at the same time. (As Crenshaw demonstrated, the challenges faced by Black women did not necessarily boil down to a simple sum of the challenges faced by white women and those faced by Black men.)” (71)

In other words, intersectionality posited that different oppressions intersect, creating unique experiences for members of multiple identities that are greater than the sum of their parts. Anyone attempting to seek out justice on behalf of people who hold multiple identities among oppressed groups needs to listen to the testimonies of people in those situations so that the unique ways in which they experience unjust treatment can be better understood and remedied. Existing laws or rules that forbid certain kinds of discrimination based on single group identities may fail to address the actual injustices faced by the many members of society who hold multiple identities at once.

As with his account of the difference between standpoint epistemology and its more popular emergent variant, “standpoint theory,” Mounk also argues that intersectionality evolved in academia and in left wing political movements in ways that led it to take on new claims that he finds problematic. Here’s how he describes that:

“When scholars and activists use the term “intersectionality” today, they usually think of it as a kind of logic of political organizing. Drawing on Crenshaw, they emphasize that different forms of oppression reinforce each other. Then they draw the inference that effective action against one form of oppression requires effective action against all. As a result, intersectionality is now often taken to imply that activist movements should require their members to sign up to a very broad catalog of causes and positions — the necessary stance on each being determined by the group that is most directly affected. (71)

Ibram X. Kendi, Robin DiAngelo and others: Dismantling Racism, Sexism, etc.

Finally, Mounk spotlights the work of thought leaders like Ibram X. Kendi and Robin DiAngelo who synthesize many of the prinicples of identity politics into teachings and trainings aiming to dismantle racism, sexism and other -isms and -phobias. Their writings, teachings and, in DiAngelo’s case, popular Diversity, Equity and Inclusion trainings for corporations, universities and major non-profits have been a part of what Mounk calls identity politics’s “short march through the institutions” beginning in the 2010s and continuing now.

DiAngelo and Kendi became highly sought-after public intellectuals after the brutal murder of George Floyd by a white police officer in 2020. DiAngelo’s book, White Fragility, became a bestseller. Her DEI trainings emphasize ideas such as: white people are all racist because racism is simply the normative culture they’ve imbibed since birth. The moral task of white people is to engage in a lifelong education of unlearning racism.

This process includes: recognizing the myriad ways in which white Americans enjoy racially based privelege; learning to defer to people from other racial groups regarding social and political changes they favor and give their support to those positions; and, understanding that their own discomfort with dismantling systems of racism is part of the phenomenon known as white fragility. This approach to DEI encourages a kind of “progressive separatism,” in which some of the work that is done in breakout groups is done by having participants gather in groups according to racial identity. It also emphasizes cultivating awareness about harms to the psychological safety of historically oppressed groups in everyday settings. For example, it explores the phenomenon of microagressions in attempting to educate people about how systemic racism often plays out in the day-to-day.

Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist also became a bestseller during this period. According to Mounk, Kendi presents the argument that there is no such thing as being “not racist” — either a person is racist or antiracist. Being antiracist requires learning a set of important truths and committing to action in service of dismantling racist systems. People who don’t make the effort to be antiracist are, despite their best intentions, actually racist (because they are perpetuating a racist order even if they don’t realize it.) The way to know whether or not a person, policy or institution is racist or antiracist depends on whether the things they advocate will serve to decrease the gap in power and wealth between oppressed racial groups and whites or not.

Mounk also adds that in left wing political circles that embrace Kendi and DiAngelo’s work, there’s a prevailing atmosphere that discourages dissent from a political orthodoxy based in identity politics.

Stay tuned for part 2, in which I’ll present Mounk’s description and critique of identity politics, followed by his proposal for an alternative progressive American politics. Then I’ll wrap up with my own reflections and questions.

Comments are open, but again, I ask if people could avoid talking specifically about the current Trump Admin or the last election, because it messes with my OCD something fierce.