A Biblical Text Adventure: "A still, small voice."

Another exploratory biblical text adventure

Countless millions of English readers have found inspiration and comfort from the King James Bible’s translation of the last bit of 1 Kings 19:12. In the KJV (King James Version), the translators took a difficult Hebrew phrase, kol d’mamah dakah, and rendered it as “a still, small voice.”

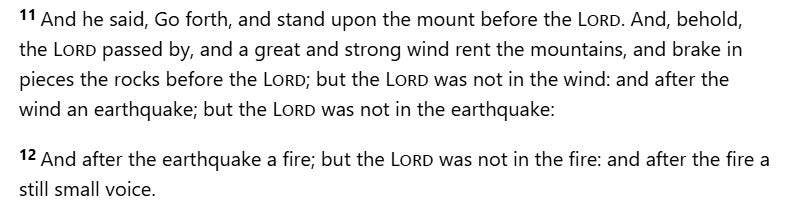

Here's the KJV translation of the passage that includes this famous phrase:

It’s a beautiful translation, especially considering, as I said, that kol d’mamah dakah, presents challenges to translators.

Kol isn’t difficult — it usually means “voice” and it is used in other places in this biblical scene to mean “voice” (as opposed to “sound,” which some translations use).

D’mamah only occurs three times in the Hebrew Bible: once in this passsage, once in Psalms 107:29 (in which God calms raging seas into murmuring stillness), and once in Job 4:16 (in which the speaker says that he heard a murmur or whisper). So our options for English are in the arena of a whisper, a murmur, or the particular stillness of calm waters.

Dakah means something like small, thin, withered or fine (like dust). We meet this adjective in the Exodus story describing the first time the newly freed Hebrews witnessed manna on the ground. Exodus 16:14 reads: “When the fall of dew lifted, there, over the surface of the wilderness, lay a fine and flaky substance, as fine as frost on the ground.”

I’m not going to get into the grammar of how these three Hebrew words are put together, but let’s just say that a translator would have to make some decisions. You could make a case for a translation like: “…but God was not in the fire. And after the fire, a voice — a thin whisper.” Or you could do what the KJV did, and treat the two words after kol as both modifying it. And you could prioritize trying to express something of the alliteration and onomatopoeia in the Hebrew — d’mamah dakah. If you did that, you might come up with: “A still, small voice.”

Everett Fox, the contemporary biblical translator who tries to make his translations express some of the sounds, rhythms and idioms of biblical Hebrew, has a note in his translation of this verse. (He went with “still, small voice.”) He writes:

I … contemplated using “a mild murmuring voice.” But the King James Version’s “a still, small voice” has never been surpassed, and retains much of the mystery and ambiguity of the Hebrew, in which the prophetic experience encompasses both awestruck silence and speech.

Thanks for the biblical translation mini-course, Maurice; but, what’s going on in this scene?

Oh - right. It might be helpful to explain that. Sometime approximately during the 870s BCE, there were two different Israelite kingdoms in the Holy Land. In the south was the Kingdom of Judah, home to 2 of the 12 tribes of Israel, with its capital in Jerusalem. In the north, the Kingdom of Israel, home to the other 10 tribes, with it’s capital in the city of Samaria.

Elijah was a prophet who addressed the people of the northern kingdom, Israel, including the idol-worshipping king, Ahab and his wife and partner in idolatry, Queen Jezebel. When Jezebel had the prophets of the God of Israel slain and threatened to make Elijah next, Elijah fled for his life. He ends up going on a long journey, deep into the Sinai wilderness, where the Hebrew slaves had once wandered with Moses for 40 years.

Knowing he is the last remaining living prophet of Israel’s God, and suffering from starvation, Elijah becomes demoralized to the point that he actually asks God to just end his life. Through an angel, God gives Elijah food and drink to keep him alive and even give him abundant strength for his journey.

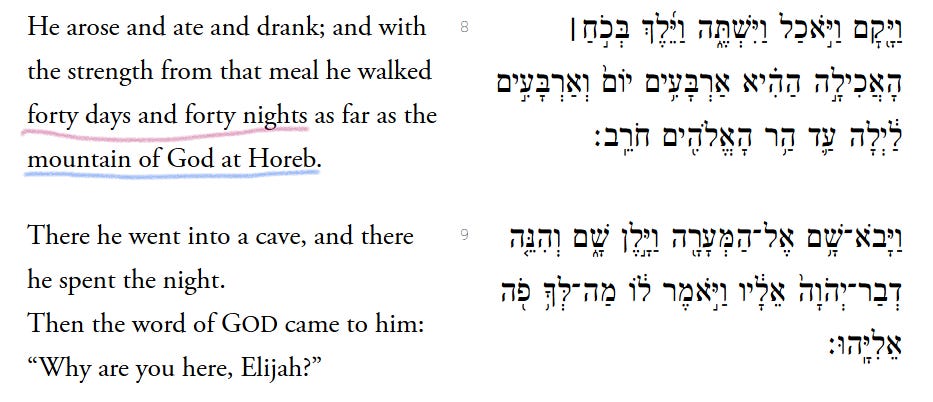

Elijah heads for the wilderness mountain of God, the site of God's revelation of the Ten Commandments to the entire assembled people — the mountain called both Sinai and Horeb in the Hebrew Bible. (Here it’s called Horeb.) Elijah hikes for — wait for it — 40 days and 40 nights, when he finally arrives at the foot of Horeb.

Elijah is now at the same site where long ago God appeared before Moses and the recently freed Hebrew slaves amidst terrifying thunder, lightning, smoke and horn blasts, the very place where God declared the terms of God’s covenant with Israel.

Let's pick up the story with the 2023 Jewish Publication Society (JPS) translation. The “he” in the passage is Elijah. I’m breaking up the following passage into subunits so I can comment on them as we move through it.

The text has just connected itself to Moses’s 40-year journey with the freed Hebrew slaves, only this time Elijah is reversing that journey.

I think the first intended audiences for this story would have felt dread upon hearing this. They may have thought something like:

Uh-oh. If God led Moses to this mountain, made a covenant with his people there, and then accompanied him and the people through their 40-year journey towards the Promised Land, then maybe God can unwind everything by leading another prophet, Elijah, through a symbolic reversal of the entire 40-year trek, leading back to the mountain where the covenant was sealed.

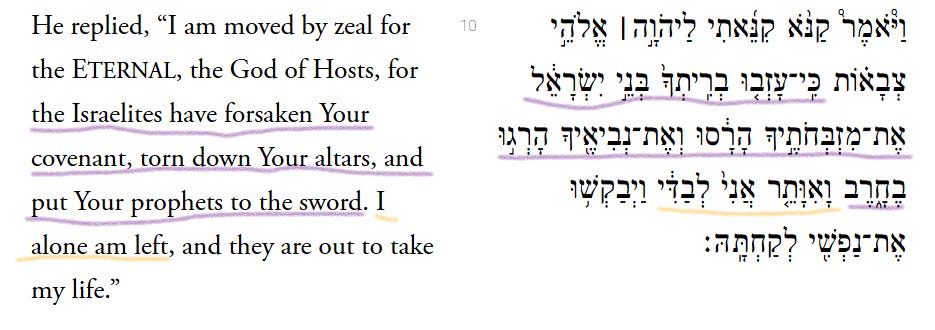

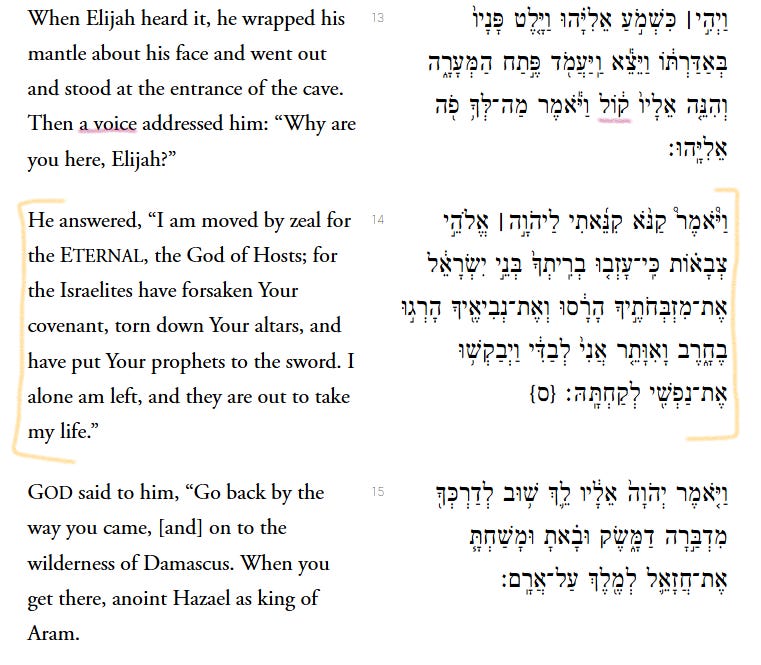

Anyway, here's Elijah’s reply to God’s question “what are you doing here?”

I’m struck by the purple underlined part above — Elijah’s bitterly frank summation of what the Israelites have done. Perhaps Elijah means only those in the Northern Kingdom of Israel and not the residents of Judah, but it’s still damning. It’s an accounting of his own people’s complete moral depravity.

The Hebrew Bible, here and in so many other places, tells stories of moral failures of the worst kind by the nation it was written by, for and about. I sometimes wonder whether there exists another people on Earth whose canon of sacred texts is so brutally critical of itself.

The Hebrew Bible’s recurring descriptions of the Israelites’ many instances of idolatry, greed, oppression, hypocrisy, corruption and violence will end up playing the role of moral warning for the Jewish people; but, ironically, these intensely negative portraits of the Jews will also end up influencing some of the anti-Jewish demonizing that is found in certain places in the New Testament and the Qu’ran. This is a complicated observation that is probably deserving of its own blog post. I’m not going to dig into more deeply into it here.

Instead, I’ll move on to note the words underlined in yellow above. “I alone am left,” Elijah says. Or more literally, “And I remain, all alone.” Like the earlier passage about Elijah’s 40-day-and-night trek to Horeb, this statement by Elijah also evokes another famous biblical text. The Hebrew word that translates to “and I remain” here strongly alludes to Genesis 32:25.

In that scene, the Book of Genesis’s Jacob is getting ready to meet up with his brother, Esau, for the first time in years, and he has sent the other people in his entourage and his livestock ahead of him. It’s at this moment that the text says “and Jacob remained, all alone.”

Knowing that Esau hates him and can slay him if he wishes, Jacob ends up spending what might be the last night of his life alone in the outdoors. This is the night that God, or an angel, wrestles with him all night, dislodging his hip, but unable to defeat Jacob. Jacob wrests a blessing from his celestial opponent, and the divine being gives Jacob a new name, Israel.

In any event, we have a strong literary connection between the moment of Jacob’s ultimate resignation and dread and the moment when Elijah tells God that of all the true prophets, he remains, all alone.

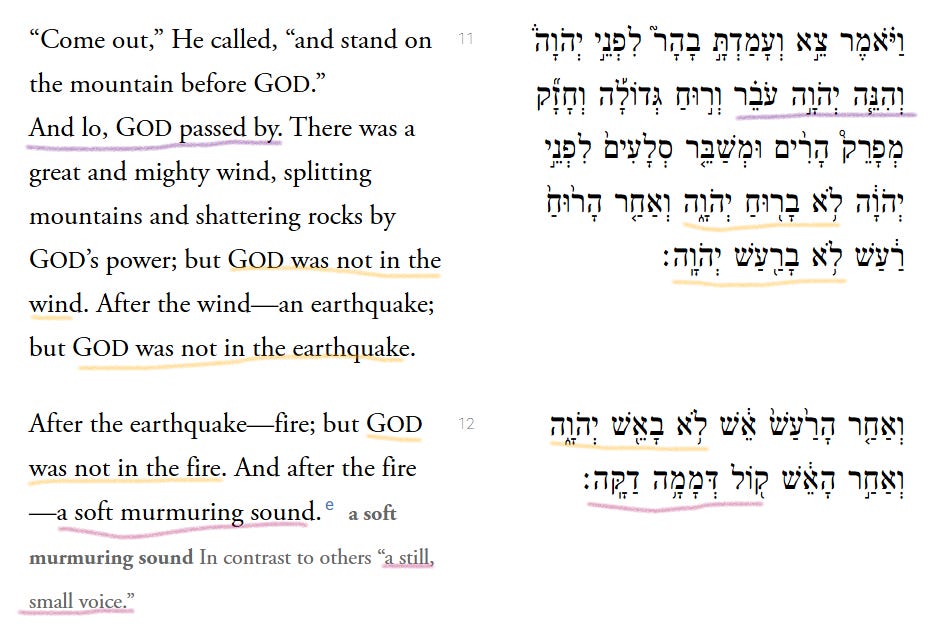

The first underlined words in purple above — “And lo, God passed by” — connect this story to Exodus 34. In that scene, Moses has followed God’s instructions to carve a set of stone tablets to take up the sacred mountain. The reason Moses has to carve these tablets is because he shattered the set God originally gave him, with the Ten Commandments inscribed upon them, when he saw the Hebrews worshipping the golden calf. This is God giving the Hebrews a second chance.

Moses heads up the mountain with the two tablets, and God descends to the mountain in a cloud. Then, God passes before Moses, proclaiming God’s special name (YHWH) as well as a series of God’s attributes. Moses bows low and prepares for God to dictate the terms of the covenant that God is giving the Hebrews a second chance to keep faithfully (spoiler: they won’t).

So now Elijah is here, on the same mountain, and God reenacts the act of taking form and physically passing before a prophet with Elijah. Again, the first intended audiences for this story probably felt a rush of dread when they heard that God was passing before Elijah on the mountain. Why?

Because when God passed before Moses, it was in order to give the Israelites a second chance after the golden calf disaster. But at that time God warned Moses and the Israelites that if they violated the covenant again — especially the part about worshipping other gods — they would bring ruin down upon themselves.

Well, now Elijah is here, and the Israelites have been up to their eyeballs in worshipping a different god, Ba’al. The audience is wondering — will there be a third chance for our people? What’s going to happen next?

What happens is as artfully written as it is surprising. The verses underlined in yellow above offer one of the most mysterious and unique moments in the entire Hebrew Bible.

Three times the narrating voice tells us where God was not: not in the wind, not in the earthquake, not in the fire. Each time that the text says a place where God was not, the suspense builds. Where was God if not in any of these wondrous places?

All we are told is: “After the fire — a soft, murmuring sound.” Or, “after the fire — a still, small voice.” Kol d’mamah dakah.

Was God in that soft, still sound? It seems like it, from the context of the overall passage. But it’s also possible that that sound was just what Elijah heard after the wind, earthquake and fire. The text doesn’t say “and God was in the still, small voice.” We’re left with one of the most wonderfully evocative and ambiguous texts in the Hebrew Bible. Let’s see what happens next.

After the last verse in the selection above, God gives Elijah some additional instructions involving anointing different individuals in different lands, as well as a directive to appoint Elisha to be the prophet who will take over Elijah’s duties.

But let’s linger on verse 13 above, the first verse in the selection. The English translation says that Elijah “heard it,” presumably meaning the still, small voice. A more precise translation would read: “When Elijah heard…” or “When Elijah listened…” There's no “it,” in the Hebrew, though it could be implied. The verse continues to say that Elijah wrapped his mantle around his face and walked to the entrance of the cave, whereupon a voice asks him why he is there.

We could translate as follows:

…but God was not in the fire. And after the fire, a still, small voice. And it was when Elijah listened that he wrapped his mantle around his face and went out and stood at the entrance of the cave.

This way of translating implies that God was in the still, small voice. Elijah witnesses (and intensely experiences) the great wind, the earthquake and the fire. He may be trembling and overcome, but the narrator tells us (and we presume Elijah understands as well) that God was not in any of these loud and tremendous events. After the fireworks are over, there is this “still, small voice.” Is God in it? we wonder.

The key thing that happens next is that we’re told that some time after the still, small voice was there, Elijah listened. And when he did, he behaved as a prophet would if they expected to be at risk of seeing God’s form and dying immediately from the encounter. He covered up most of his face and his field of vision, and stood at the cave’s entrance.

One thing worth noting is that it seems like Elijah had to listen carefully and discern the subtle sound of the still, small voice before he was able to be addressed with new instructions from God. This is similar to Moses at the burning bush, when Moses needed to closely observe not only that a bush of dry scrub brush in the blazing hot desert was on fire, but that its branches were not being consumed by the fire. The prophet in both stories had to pay close attention to something wondrous but subtle.

That’s interesting. But what’s up with Elijah repeating himself word-for-word in the selection above?

Yes, I figured you’d notice that. You’re referring to the verse that I drew a yellow bracket around above. After the stunning moment involving the wind, earthquake, fire and still, small voice, God again asks Elijah what he's doing there, and Elijah repeats verbatim the response he gave earlier about Israel’s sins and his being the sole remaining prophet alive.

Is this some kind of seam in the Hebrew Bible, where the redactors (final editors) sewed together segments from two different versions of this story they had received, and the result was a final text with an oddly placed repetition of a key verse? (That's the explanation that is sometimes supposed when there are odd seeming repeated quotes or stories in biblical narratives.)

I don't think that explanation tells us enough about what’s happening here. The repetition of Elijah's quote about Israel’s sins and his being the sole remaining prophet alive is front and center in this narrative. Even if the redactors were merging two versions of this story into one, the decision to have the final version include this word for word repetition of Elijah's response to this question was definitely intentional.

So what's happening that leads Elijah to say the exact same thing again here? The text wants us to wonder. Was Elijah dumbstruck by the intense experience he just had with God passing by him so that all he could do was repeat the last thing he had said?

Or did something supernatural happen with time while God passed before Elijah, so that this repetition of the question God asks and the answer he gives is not a repetition at all? Maybe Elijah was pulled out of time into the divine realm of eternity, where time doesn't exist, and then returned to regular time after God passed before him. Now back in regular time, the story picks up right where we were before, kind of like a film cutting back to the moment we were watching after showing us a flashback or a hallucination from a character’s point of view.

This text doesn't give us many clues to help us understand what has just happened. It's a jarring and disorienting element of a story that reveals amazing things but also withholds a lot. That's by design, it’s this kind of great writing that helps make the story unforgettable.

How can this story help us now?

Well, crap. I was hoping you wouldn’t ask me that.

Okay, here’s my best attempt at an answer. I can’t claim it’s all that original.

The world we live in now is full of loud gusts of wind rattling our society’s democratic foundations, earthquakes upending the bedrock of the rule of law, and as for fire — well, let’s face it: the country’s in the hands of a madman who likes to set all kinds of shit on fire. I know this even though I severely limit my news intake because of my severe OCD. I still feel the wind, the earthquakes and the fire.

Sometimes, we probably despair over whether we’ll ever get a moment’s peace when we could listen for a still, small voice of hope and guidance. (Now that you’ve got me going, I think this story can help us.)

This episode in the story arc of Elijah’s time as a prophet tells us that sometimes the wrong people seize power and then turn their weapons upon those who speak truth to power, even eliminating most of the dissenters. It’s telling us that even if there’s only one person left who refuses to submit to their authority and their beliefs — or perhaps, even if it were to feel to us like we were the only defiant person left — there are still useful things we can do.

If the homeland is lost to tyranny and falsehood, there’s still the wilderness, desperate and dangerous though it is.

If the mountain of God in Jerusalem is lost to the wicked, there’s still the mountain of God in the desert, though it be a long journey’s distance.

And when tyrants rule by fear and intimidate through the use of loud pyrotechnics, it is still possible to wait for the racket to die down, and then to focus on careful listening. The still, small voice is there.

The difficult part is being able to listen.

Once we listen and find the connection between us and the faint signal of the Divine spirit, we can begin to discern what to do next. Maybe only just that much will become clear, but that’s enough.

When Elijah hears God’s instructions for what to do next, they include him annointing someone else to take over his prophetic role — Elisha. For us, this part of the story can teach that the sacred work to be done to restore justice and democracy may take more than one generation of prophets and ordinary people staying true to the values of human dignity, equality under the law and the banishment of corruption.

We can’t pick the times we live in, and it’s truly terrifying to live in a time of the rise of truly wicked men (I don’t use this language lightly). But if we can figure out what we can do to work for our values in such times, we can build a foundation of inner serenity guided by God’s still, small voice. May all of us struggling to do just that find each other, share our experiences, and forge new bonds of community and solidarity aimed at building a better future for our beloved nation.

Thanks Maurice for your clear and uplifting message for us. We need all the inspiration you can provide in these uncertain and troubling times. Best to you and your family for a bright and happy Chanukah :)

Maurice, thanks for this. Really helpful for me.